TRAVEL IN ALGONQUIN PARK

The first Europeans to travel throughout today’s Algonquin Park were explorers such as Champlain and David Thompson. In their wake came the trappers, lumbermen and settlers, roughly in that order. Indigenous to the Algonquin Region was the lightweight birch bark canoe, a mode of travel vastly superior for exploration than tramping through dense bush. A canoe can carry more supplies than one’s back and is much easier to paddle than it is to brush out a trail through the wilds. Thus the Indians, explorers, trappers and lumbermen took full advantage of the network of water bodies for travel and transport.

With the developing timber trade, tote roads were cut out to transport goods and supplies to the camboose camps. And so, when the harvest was in, the lumbermen left their farms and headed to the bush for their winter’s work. They walked, or when possible hitched a ride with a teamster. Real horse power skidded logs to dump sites on the frozen rivers and lakes to await the spring thaw when meltwater power would transport them to the mills. Perhaps this was more environmentally friendly for the lumbering was restricted to two seasons.

In the 1890’s the stage travelled from Eganville to the Basin Depot three days a week carrying passengers, mail and supplies. Transporting the horses to the interior sometimes proved a challenge. They would wade shallow streams and where the depth was too great, their harnesses would be removed so the horses could swim or, if available, they would be transported across a large body of water on a large raft called a scow.

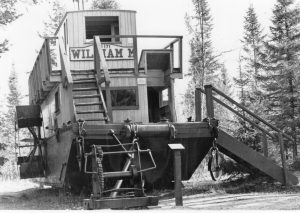

To move log booms across large bodies of water huge rafts designed to accommodate men and two horses were constructed. A pointer boat would tow the raft, an anchor would be cast out, and the horses would wind in the log boom using a capstan. The steam driven alligator, a rear paddle wheeler capable of skidding itself across portages, replaced the horse powered raft. The William M that worked Cedar Lake and was owned by the Gillies Brothers is on display at the Algonquin Park logging exhibit.

During logging drives ‘sweepers’ maneuvered the logs from pointer boats that came in two basic sizes, the 22 foot half-ton baby and the larger 50 foot model. In 1921 Archie McAdam, a bush foreman for J.R. Booth, used a gas powered pointer at Kiosk.

When several Algonquin log drives came together on the Ottawa River the men constructed a huge raft which could accommodate a mini tent city to temporarily house the drivers. It also included a cooking setup similar to that in a camboose shanty. The men steered the raft with 30 foot oars and set up sails to compliment the river’s running power.

Like the Indians, explorers and trappers the lumbermen wore snowshoes to keep atop the deep winter snows while travelling the bush. After the creation of Algonquin National Forest in 1893 (it became Algonquin Provincial Park in 1913) park rangers patrolled on snowshoe looking for poachers. One ingenious trapper donned a pair of stilts in order to sneak into the park after trapping had been banned. Another put his shoes on backwards in an attempt to fool the Rangers.

The train revolutionized timber extraction for now it could be a daily affair. No longer did it depend upon the natural order of the seasons. And it became a vital link between the park and the outside world. The train carried logs out of the park and transported tourists in, on a daily basis. Except for the traditional modes of travel, the train became the only way to get in and out of the park.

Have you ever wondered why there are barrels at train bridges?

The original bridges were all timber. Steam locomotives spewing hot cinders often started fires. Barrels full of water were placed to help should the bridge catch fire.

The Buffalo Flyer introduced many tourists to Algonquin Park. It originated in Toronto but was so named because many Americans travelled from Buffalo to Toronto in order to get to the park. It would stop along the route to drop off or pick up campers as requested. Canoes, packs and camping gear occupied the baggage cars.

More than one “3 wheeled speeder” travelled the rails carrying Romeos in search of their Juliets. Such was the case of the parents of a friend whose father travelled by “speeder” through the park to court his mother.

But there was a sad side too, such as the time when Nurse Molly Colson received an urgent plea for help from a man whose wife was expecting. In dramatic Hollywood style they raced the rails on a “speeder” amidst an atmosphere charged with lightening flashes and howling winds. “Ma God, ma God,” the man kept moaning, “my wife and child are dying.”

In a “wretched little shack” on Rock Lake Colson found that the baby was dead, mother was very ill and one of the children was suffering convulsions. Colson nursed the mother for four days and made arrangements for the family to move to a Ranger’s house where the woman could receive better care.

The railway’s time in Algonquin Park was very brief for by 1953 it was out of business, closed forever. Today, all that remains as a reminder of the blood, sweat, tears, toil and tragedy are the rail beds now used by cross country skiers, hikers, bikers and turtles that consider it their private nursery.

Not only did the lumbermen use horses in the park. Tourists heading for Mowat Lodges often stepped down from the train to be greeted by lodge owner Shannon Fraser and his horse drawn hearse that he used to transport his guests to their holiday home. Those heading to other lodges often had the choice of travelling by rowboat, canoe or horse drawn wagon over brain jarring corduroy roads.

Sometimes park Rangers travelled their winter patrols by dog sled although many found the dogs a nuisance. Extra time had to be expended training, feeding and caring for the dogs – the year round. And because the dogs had to be kept tied up their incessant howling won them few friends. The arrival of the beaver aircraft diminished their need.

With the arrival of the outboard motor came a controversy perhaps as spirited as that which surrounds “sea-doos” today. The Smoke Lake Leaseholders Association requested that trolling from boats propelled by mechanical power be prohibited. In the spirit of fair play perhaps they suggested that fewer fish would be caught if “paddle only” power were employed because once tired the canoeist would head for shore whereas mechanical power would empower fishermen to press on until their quota was caught. Outboard motors in the park remain a controversy to this day.

Planes and pilots from the Great War revolutionized park fire patrols. Although they were employed irregularly (since 1922) such craft as the Avro 504 K, the Curtiss H52L (a flying boat with a pusher type engine), and a Fox Moth proved the value of an air fleet for fire and other patrols. The first flying Superintendent F.A. MacDougall could view the park in a matter of hours whereas Superintendent Bartlett spent as many as six weeks viewing the park on patrol. The park aviators literally flew into the future leaving, in their wash, much tradition for both historians and romantics to masticate.

Man’s most revolutionary invention affecting Algonquin Park may arguably be the automobile. In 1916 Superintendent Bartlett recommended building a highway to follow an abandoned railway line but the idea took a back seat to war time priorities. In 1933, however, Frank A. MacDougall, the first flying Superintendent, announced that a road would be constructed and so the F.A. MacDougall Highway (#60) opened the park to automobiles permitting the average citizen driving access into the future of Algonquin Park.

James Wilson was Superintendent of Queen Victoria Park, Niagara Falls (1886-1908) when asked

to tour Algonquin and to suggest ways to improve it. Following a lengthy canoe trip one recommendation still stands out.

“Wage war on gulls and loons that annually destroy large numbers of young trout…the birds have no commercial value and their depredations largely outweigh other considerations.” Imagine the park today with no natural loon calls.

In 1901 Timothy O’Leary, Chief Ranger, guided some artists on a canoe and sketch trip into the park interior. Thus began a tradition that would continue until 1917 and foreshadow the Group of 7’s Algonquin connection. Artist Tom Thomson “had the wilderness in his blood” and although he dabbled at other park pursuits to pay the bills it was his art that best revealed his passion for nature. It was by the medium of the paddle and portage that he was able to immerse himself in such a passion.

Perhaps after his death Thomson took one last paddle? Mrs. Northway of Nominegan Lodge and her guide Alphonse were paddling towards the Ragged-Smoke Lake portage when they saw a man in a yellow shirt paddling towards them. As was customary the canoeists waved a friendly greeting only to have the other canoeist vanish. Lawren Harris, a fellow artist and friend of Thomson, insisted it was his spirit.

The canoe may best symbolize travel and transport with Algonquin Park’s past. Since then the railroad has come and gone and other mechanical devices continue to revolutionize our concept of travel. However, once park visitors arrive the majority continue the romantic tradition of travelling and exploring by canoe. The canoe may well be of the past but it is also an important part of our present and without any clairvoyant claims this writer believes that the canoe will continue to be the future choice of travel within Algonquin Park as modern day Romantics continue to explore the park’s network of waterways.

This article was first published during the Fall of 1992.