BANCROFT SHRINERS AFTER DINNER SPEECH

Wasn’t that a fine meal? It reminds me of two down and out Irishmen, Casey and Murphy. As they passed a restaurant they spied a sign that proclaimed: “If we don’t have it we’ll pay you 100 pounds.”

“Let’s try it,” said Murphy.

“We haven’t got any money. What if we have to pay?” asked Casey.

“We can always do dishes.”

So, in they went and sat at a table. An immaculately dressed waiter appeared.

“Would you like to order?”

“We’ll have elephant kidneys on toast,” ordered Murphy.

“Certainly, sir,” said the waiter, nonplussed.

Five minutes later the waiter returned, plunked 100 pounds down on the table and said: “It’s your lucky day. We just ran out of bread.”

THE IRISH CONNECTION

In the 1860’s the government of Canada provided free grants of land along the Old Hastings Road. In the late 1840’s the great Irish potato famine drove many from Ireland to escape starvation and a hopeless future. They were referred to as “shanty Irish” whereas the well-to-do were called “Lace Irish.” Umphraville (aka Umfraville), on the Old Hastings Road, between Ormsby and L’Amable, was named after a village in Ireland and it became a predominantly Irish settlement. In researching local St. Patrick’s Day celebrations I came up virtually empty. It has occurred to me that initially, due to the hardships, Irish memories weren’t so wonderful whereas to-day’s lifestyle lends itself to such sentimental celebrations of the “good old days”. However, I did find a notice that in 1863, 500 Orangemen rioted in Peterboro to stop the St. Patrick’s Day parade and Irish Fenians were gathering on the U.S. border threatening to invade Canada.

In 1861 Michael Doyle operated a store and was the postmaster at Doyle’s Corners. Then the name changed to Tara after the name of a hill in County Meath, which means “hill homestead.” In 1863, the name changed briefly for 4 months to Oxendin, after which it became Maynooth. Now the CBC calls it “MAY-nooth.” The local Canadian pronunciation is “Ma-Nooth” and in Ireland it is “Ma-Nooat.”

There is some debate whether Maynooth is named after Ma-Noat in County Cork, Ireland, or Maynooth in County Kildare, near Dublin, famous as the site of St. Patrick’s College where the secular clergy of the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland receive instruction.

In 1879, Bancroft was first a Police Village with three police trustees. It wasn’t incorporated until 1904. Co-incidentally, we could have celebrated both 125 years and 100 years simultaneously.

Other Irish names are found in places such as Mayo and Limerick. Wicklow was named after Wicklow County, south of Ma-Nooat in Ireland. In 1891, Fort Stewart was either named after Tavern keeper John Stewart or Fort Stewart Ireland, although in Ireland it was in County Donegal, not Carlow. The “echo” theory is that it is named for both.

My next contribution is courtesy of Marguerite McColl, born in 1909. The author of this next piece signed himself – I.W.T. See if you can determine its meaning. In real life the author was Warren Davy, son of Adam Davy, Mrs. McColl’s first cousin who was born circa 1895. After returning from WW1 the government assisted him in obtaining his teaching certificate. He moved to, and taught in, B.C. Keeping with the Irish connection this is called “The Dublin Revolt,” by I.W.T.

The insurrection in Dublin that occurred during the summer of 1916, its cause, events, and the historical significance have no part in this article except for the fact that it almost involved a body of Canadian soldiers of which I was one.

Everyone who has made himself familiar with the history of Ireland knows that this was but one of a long series of events that disturbed the relations between part of the people of the country and the British government and that culminated in the final settlement from which emerged the present government of the country. (This was penned in the early 1960’s.)

This revolt, if it can be called by that name, drew especial attention because it occurred at a time when Britain was fighting for her very existence. There is no doubt that the government was sorely tired and sought the readiest means to suppress the trouble but the Canadian officials, whether military or governmental, who offered or agreed to the involvement of a Canadian force in quelling the insurrection were, in my opinion, making a terrific error that could have led to long and bitter recrimination of the Canadian government. That it didn’t reach that stage was due, not to any fore-sight or afterthought on their part, but to the early collapse of the revolt when a destroyer moved up the Liffey River and fired a few shells into the area which was the centre of the disturbance.

I have had no access to official documents and know no more than I have stated above except for the actual preparations in which I took part.

This is what happened.

The Canadian Third Divisional Artillery was stationed at Witley Camp in Surrey. Training had been going well and we had recently returned from our trek to Salisbury Plain for firing practice. Then one morning everyone was startled by the news of an uprising in Dublin. The next day we were informed that a composite battery of Canadian Field Artillery would be sent to help quell the revolt. Two men would go from each sub-section of the batteries in the division. For some reason unknown to me, I was chosen as one of the two from A sub-section of our battery.

The new battery was quickly assembled, positions were assigned, and we started a period of intensive training which went on without interruption for several days. It was hard work for there was little spare time permitted. We were expecting instructions to embark at any moment when suddenly, as mentioned above, the uprising collapsed.

I, for one, breathed a sigh of relief. While I was just as ready as anyone else to get over to France to face the real enemy, going to Ireland was an entirely different matter. Being one quarter Irish by descent, I had no desire to become involved in a fight there in a cause about which I knew very little at that time.

About two years later I visited Dublin and in spite of official advice to the contrary I walked through some of the area which had been shelled by the destroyer. Although I was able to see some evidence of the shelling, the damage hadn’t been extensive.

Before I finish I have two short stories.

A tourist pulled into a Petrol Station. “Check the oil,” he said.

“Sorry, we don’t do that.”

“Well, filler up then.”

“Don’t do that either.”

‘What kind of a station is this?”

“Oh, we’re a front for the IRA.”

“In that case, blow up the tires.”

Henry Ford’s parents apparently came from County Cork, Ireland. During a visit some locals approached and asked if Mr. Ford would care to donate to the new hospital. The great Philanthropist agreed and wrote a cheque for 5000 pounds.

Next day the front page news proclaimed: “Henry Ford donates 50,000 pounds for the hospital.”

Well the locals rushed right over, apologized for the error, and said that they would immediately correct the error to 5000.

Mr. Ford asked how much the hospital would cost to build.

“$50,000 pounds,” they responded.

Mr. Ford ripped up the cheque for 5000 pounds and said he would contribute 50,000 pounds if they would grant his one request.

“Certainly!”

“I want a quote mounted above the entrance.”

“Anything. What would it be?”

“I came among ye and ye took me in.”

Thank you and good night.

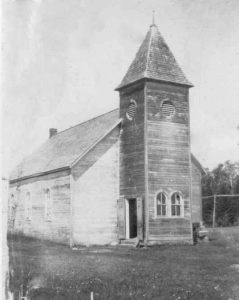

Featured image – cabin along the Old Hastings road.