MOOSE TICKS 1984

Dr. Ed Addison of the Research Branch of the Maple District Office of the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) was researching moose ticks in Algonquin Provincial Park. Essentially, he wanted to know if moose ticks kill moose.

Some Background

Ed’s mother, Ottelyn, was the daughter of Mark Robinson, Chief Park Ranger in the Park. As a little girl she knew Tom Thomson – the artist. You may wish to read her books. As you can see, Ed’s roots are within Algonquin.

During 1956, in the Swastika/Cochrane area, a fur trapper found 38 dead moose in his trapping zone. All were covered with ticks. Wildlife author Ernest Thompson Seton (“Wild Animals I Have Known” – based upon his childhood ramblings in the Don Valley) considered ticks to be a problem to moose. In 1869 moose ticks were first mentioned in Nova Scotia in an article which referred to the Whisky Jack (Canada Jay) as the “tick bird” because it ate these ticks. Ticks being a problem to moose has an historical setting.

During Dr. Addison’s slide shows we saw ‘mangy’ moose with large patches of raw skin. One had been seen in the same place for two days slowly dying before trappers ended its misery. It suffered from ticks.

In the late 1970s, 100+ dead moose were discovered in the province of Alberta. One carcass was covered with an estimated 173,000 ticks. Further, hundreds of moose died there in the spring of ’83. In March, April and May the average number of ticks found on these “ghost” moose numbered 52,000.

During March of 1979 there was a healthy moose population in Ontario’s Alfred Bog. Five dead moose including one with very little hair were found. It was bitterly cold. One adult moose carcass had 83,000 ticks; a calf 86,000.

The MNR established a moose tick research facility in Algonquin Park to study this problem. In fact, it used the pens formerly used for Dr. Pimlott’s wolf research some years earlier. Dr. Addison began with 3 orphan moose calves. Two survived, apparently something of a success in itself. Moose were so very hard to obtain that deer were substituted but that failed as the ticks are prejudiced to moose. They soon abandoned the deer.

Moose ticks lie on their backs, 8 legs in the air and await movement before attaching themselves to the source. While collecting ticks some naturally attached themselves to the researchers but upon discovering that ‘they’ were not moose the ticks then dropped off. How the ticks can identify a moose is yet unknown.

Moose ticks hatch mid-summer and climb aboard in the fall. They climb bushes and wait, sometimes as long as until December. The ticks live off the moose throughout the winter.

In March the female ticks, who require lots of blood, suck voraciously on the moose host and grow to the size of one’s thumb nail. Engorged with blood the females then drop off – from mid-March to May – and lay their eggs, 6-10,000 (300/day) on the forest floor. Ten thousand eggs would be about the size of a new eraser on a pencil.

Several thousand ticks will fall off where a moose beds down. In September and October should a moose pass by that bedding spot – or worse actually bed down there – the ticks will climb aboard.

To study all of the effects of moose ticks the research moose had to, reluctantly, be put down. Sufficient knowledge was learned about the rate at which a moose carcass cools that Conservation Officers, armed with a special thermometer, can check an ‘opening day’ carcass and determine whether it was killed in or out of season. Some successful convictions have followed.

Ed’s research team learned from its successes and failures and ultimately successfully raised 18 moose calves one year; a 100% success rate.

The research also taught them that moose calve in open habitat, not in dense bush as previously believed. From May 13-26 they found 11 moose including 8 sets of twins. Twins tend to calve earlier and nature takes her toll of the young. These births took place in open habitat on a high ridge from where the moose could see for miles.

The birth weight of the orphan moose, caught for the tick research, over a 9-day period, ranged from 19 to 59 pounds. One, named ‘Tripod’ due to a broken leg, was in a cast for 5 weeks. By September the calves had increased in weight by 100 pounds.

How do the ticks kill the host moose? Perhaps a combination of factors are at play including loss of blood and the moose scrapping and rubbing in hopes of removing the annoying ticks. In such a manner the moose rubs off its protective insulating hair. Licking action followed by a freeze also has a negative impact. Moose affected by ticks have scant fat deposits internally.

How to solve the tick problem? There aren’t any ticks in Alaska or in the Scandanavian countries where there are large moose populations. There is little research available for reference. One theory believes that fewer moose hosts will result in fewer moose ticks resulting in a healthier more reproductive herd. Some ticks will survive a winter without a host but the majority will die. This may be nature’s way of naturally controlling the problem.

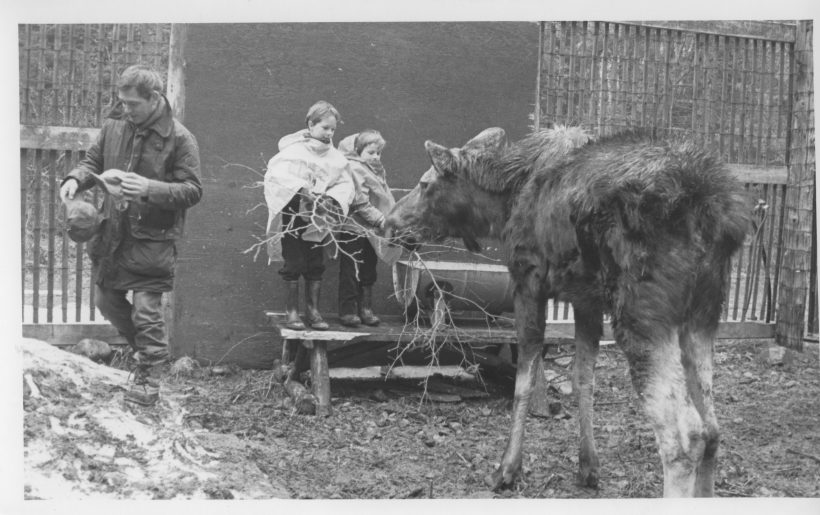

In the spring of 1984 my family and I visited Ed Addison at his research station in Algonquin Park. There were two cows and two bulls, each in its own large, separate yard. Each yard featured a shelter, water, food supplies and a rubbing bar. The 4 moose received the best TLC (tender loving care). Even their hooves were trimmed. They were to be the last of this live animal moose tick research. It had come to its conclusion.

Once the ticks fell off their hosts the moose were being sent to the Metro Toronto Zoo, to the Detroit Zoo and to Michigan. The MNR and the Ontario Federation of Anglers & Hunters (OFAH) are in the process of exchanging moose for wild turkeys.

In the fall of 1983, 40,000 ticks were painted on each of these 4 moose; a relatively small number. The ticks resemble pepper flakes. Each moose, it seems, reacts differently to ticks. One cow yielded fewer ticks while another hosted a ‘goodly’ number. Why? Perhaps some have a natural resistance? Each day the ticks were collected after they fell off the moose before the ravens could descend and feed upon them.

One cow ‘mewed’ a lot. Ed could carry on quite a conversation. AS these moose were accustomed to people we were able to feed them, pat them and check for ticks. We saw what appeared to be a large cluster of grapes attached to the cow’s anus. Each ‘grape’ was an engorged moose tick. No wonder the loss of blood could be significant.

The moose’s main predators are man and wolves. Bear also prey upon moose calves. As moose are more common in Algonquin the size of the wolf pack has increased. As a note, when Dr. Pimlott studied the Park wolf deer were more prevalent and the wolf pack averaged 6 animals. With moose they now average 9 or 10 animals. Also, as a matter of interest, Dr. Addison was also involved in Dr. Pimlott’s famous study.

Standing in the pen Dr. Addison suggested that we carry my children on our shoulders. The moose tend to regard small people as predators and naturally become nervous.

Do moose ticks taint the moose meat?

“No,” said Dr. Addison.

The moose tick research continues.