THE ALGONQUIN MOOSE AIRLIFT – Part 1 1985

One hundred and fifty years ago (1835) moose were native to Michigan. Then the settlers and loggers moved in, cleared the land and the white-tailed deer followed. When the mature trees were removed new growth generated favoured deer food. The increased population of people and deer were almost synonymous. BUT, the moose suffered. Its habitat was destroyed, moose provided table fare and the brain worm (meningeal worm) of the deer killed the moose. Deer are carriers of the brain worm but remain unaffected by it. In time the combined effect of these influences eradicated moose from the Upper Peninsula (U.P.) Michigan landscape.

Since that time better management practices and the return of mature forests have re-established excellent moose habitat in the U.P.

In 1985 there were less than 5 deer per square mile at the proposed Marquette release site. Statistics indicate that where there are 10 deer or fewer per square mile a low transmission rate of the brain worm occurs.

The Michigan DNR discussed the feasibility of re-introducing moose to Michigan with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR). The proposed site was similar to the habitat found in Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park, home at that time to 4000 moose.

The Safari Club International jumped at the chance to become involved. In Michigan there were four chapters each of which contributed $5000 and head office in Tucson donated a further $5000 to this project totalling $25,000 U.S. At the 20% exchange rate that came to $30,000 Canadian. Additionally the Safari members built custom crates to safely transfer the moose. Club members were also involved with other conservation issues such as saving the Kirtland Warbler from extinction; a good example of responsible hunters being responsible conservationists.

Ontario agreed to provide 30 adult moose over two years from the Algonquin herd with a bull to cow ratio of 1:2 or 10 bulls to 20 cows. Many of the cows proved pregnant. The size of the cows – 900-1000 pounds – and the bulls – 1100+ pounds – was much bigger than anticipated.

On Wednesday, January 23, 1985, a large, pregnant cow moose was released into the bush near Lake Michigamme, Marquette County, in the U.P. at 11 a.m. Ultimately, researchers hope that the 30 moose will be the seed stock for 1000 moose by the turn of the century.

The Capture

Approximately 20 men, with military-like precision, work as a team to capture a moose. The scenario goes something like this:

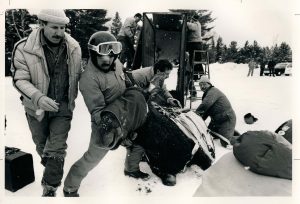

1:00 p.m. – A chase helicopter with a veterinarian takes off to seek and dart a moose. Seeing a moose they chase it onto a lake, close in, the vet darts the moose and they move off to let the drug take effect. The pilot radios base camp that they have a moose and another chopper, The Long Ranger, takes off with a crew of 4 including the pilot. In the meantime the chase chopper has landed and the vet and pilot care for the drugged moose checking its respiration, temperature, heart rate…which are constantly monitored. If there is any evidence that the moose is in danger the vet will administer an antidote. The animal’s welfare is the first priority.

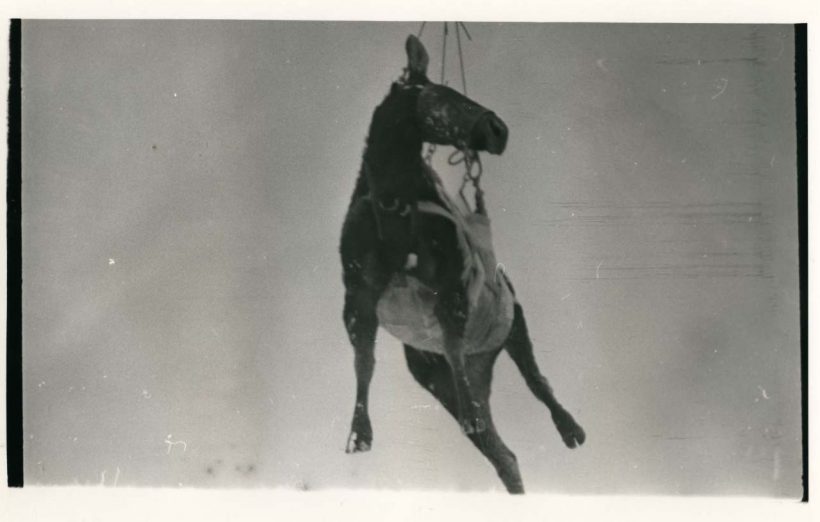

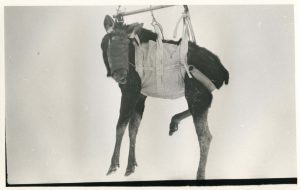

Efficiently they secure the moose in a sling, wrap its head to protect the eyes from the cold (not to mention the stress of seeing itself aloft); foam rubber is inserted in the ears for protection and the moose is ready for lift off.

The Long Ranger moves into position, lifts the moose and heads for base camp. At Mew Lake the moose is carefully lowered to rest as it would normally do when bedding down. The men place a radio collar around the neck, take blood samples, check the heart beat, respiration, temperature (100-103 degrees is normal); fecal samples are secured and the cows are checked for pregnancy. Injections of a long lasting tetracycline and vitamin E are given to combat stress. Drugs are administered to worm the moose and to rid it of external parasites such as ticks.

An Agriculture Canada vet certifies the health of the moose and gives it a series of 3 injections to reverse the effects of the tranquilizer. The first is given under the skin, the second into muscle and the third, which is quick acting, is not given until the moose is in the travel crate. This can be most dangerous. For example, one cow came out of her stupor so quickly that the Ag. Canada vet barely escaped injury.

It took approximately one hour, or less, after that first dart on the lake until the moose was safely secured and ready for its truck journey to the U.P. This certainly minimizes the stress.

To determine the animal’s weight the empty crate is first weighed followed by the weight including the moose.

The truckers carefully carried their precious cargo 400 miles to Sault Ste Marie, Ontario and then a further 200 to the U.P. release site; a journey of 16-18 hours depending upon the weather and road conditions. Every two hours the truckers stopped to check on the moose and to provide snow for them to eat to prevent dehydration. Layers of hay improved the animal’s footing and absorbed any moisture helping to keep the moose dry.

Some Comments

The relative lack of Canadian print media attention intrigued me. Television was well represented but major newspapers were conspicuous by their absence. Ray Stamplecoskie of the Eganville Leader, and I, of The Bancroft Times, were the only print guys at hand.

By contrast, at the U.P. live release site, a minimum of 75 spectators and some 40 different T.V. crews were always present. The Americans were mystified by the apparent indifference of the Canadian media.

Michigan received 29 moose and Ontario is to receive 150 wild turkeys over a 3 year period. That’s about 5 turkeys per moose.

Algonquin Park has a long history of helping to re-establish wildlife species such as beaver, marten, fisher and otter throughout North America and Europe. When I represented the Outdoor Writers of Canada at the Scout Gemboree on Prince Edward Island in 2001 I befriended Hilton Bryanton, a local trapper. At a later date he phoned to tell me he was at a meeting with the Minister of Natural Resources and they were discussing the island beaver. Noone knew where the beaver came from until Hilton told them that the beaver originated from Algonquin Park. He had read about it in my book, The Algonquin Centennial Series, which is still available.

AND FINALLY…

Ron Truman, Associate Editor of the “Angler & Hunter” magazine told me of a trip to Hudson Bay to see a Polar Bear tagging operation. He was there for only four hours. When I expressed surprise at going so far for such a short spell he said that he didn’t mind at all. In fact he was pleased that he didn’t have to stay overnight. Ron told me: “They sleep in tents with a .44 magnum under their pillow with instructions that ‘should a Polar Bear stumble into your tent fire as often as possible before it kills you. You might save someone else.’”

NEXT – Part 2