ALGONQUIN PARK – RICH IN TRADITION

One of the six original aims of the Algonquin Royal Commission in recommending the creation of Algonquin Park was to promote it as a health resort, a place of recreation. This was to be a serious attempt to keep the tourism dollar at home, to stem the tide of Canadians going abroad to enjoy their vacations and to attract foreign tourism. Algonquin Park hotels would offer clear, clean air, scenery, perhaps adventure and other opportunities unique to Algonquin. Consider wolf howls as an example. Is there a more controversial symbol of the wilderness than the wolf?

What camper has not been aroused by the howl of a wailing wolf? Interior canoe tripping campers sit around their campfire howling with gay abandon in response to a wolf’s mournful call while, at the same time, further down the lake around another campfire, other campers are howling their reply. Real or perceived, when camping the backcountry people love to imitate the wolf. Suggest that they do so in downtown Toronto and see the reaction you receive.

Officially park organized howls began in 1963. Park records estimate that 60,000 campers have heard the wolves respond during those nighttime excursions suggesting a 62% success rate. Before each organized howl, park staff scout the territory in search of an active pack. Failing this the “howl” is postponed.

What factors affect the willingness of a wolf to howl? Short of asking one, conjecture suggests that a lone wolf, separated from the pack, is more than willing, attempting to rejoin his mates. The time of the year may also have a bearing, with wolves being more responsive towards the summer’s end. Pups, in August, like to yap. Weather also plays a role. Wolves will rarely howl of it is raining suggesting that, unlike some people, they are smart enough to come in out of the rain. One researcher claims that each howl is energy draining and is followed by a brief respite during which the energy is regained. He compares it to a toilet bowl refilling after the flush.

So you want to howl? What skills do you need? Few, really. A lack of inhibition is more important. Considering that wolves have responded to the sirens of fire trucks, police cars, ambulances, and to a logger’s chain saw, you need only throw back your head and let go with your perception of a howl. Researchers will tell you that wolves have individually distinct voices which may explain their willingness to respond to the unusual.

Unique, perhaps to Algonquin Park, are the winged warriors that can attack defenseless campers at any time of the year. A sure sign of spring are the swarms of blood thirsty black flies that drive all warm blooded creatures crazy. Following the little black fly are the mosquitoes, horse flies, deer flies, sand flies (no-see-ums) and any time after October, the snow flies.

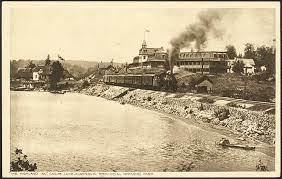

Initially travel in and out of the Park was limited to paddle, portage, snowshoe, and horse or shanks mare. In 1908 the opening of the Algonquin Park train station and Highland Inn ushered in a new era of park history improving both the convenience of travel and accommodation. In 1916 when Superintendent Bartlett proposed that a highway be built along the same route as the rail line his suggestion fell short of first base. In fact war time pressures made such an undertaking impossible. However, in 1933, when Superintendent MacDougall made the same proposal, the highway was built. The seeds of such a thought had found a fertile environment in which to germinate. And so the corridor highway, #60, now named the F.A. MacDougall Parkway, opened Algonquin to anyone who could afford the price of gas and a car. Also, arguably, it hastened the demise of train travel within Algonquin.

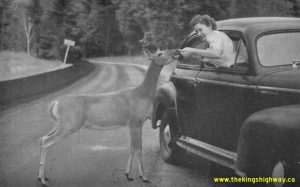

Since 1978 park records indicate that 8 million people have visited the Park. With enquiries arriving from as far away as Europe regarding this year’s centennial celebrations, park authorities are expecting record numbers of visitors this summer. Imagine, if you will, 8 million visitors attempting to travel throughout Algonquin without the benefit of a highway. Yet the F.A. MacDougall corridor highway is not without its controversy for there are those who would close it down and allow Algonquin to return to its original state.

Shelter cabins were built throughout Algonquin Park to house Park Rangers on patrol. By 1936 there were 115 cabins. F.A. MacDougall, known as the first flying superintendent, could patrol the Park by air, daily, thus reducing the need for such shelters. Interior canoeists started using these cabins but the ever present rotten apple reared its ugly head and they were vandalized. By 1950 the then Department of Lands & Forests found that it had no choice but to burn all non-essential cabins allowing the wilderness to reclaim its own.

In 1935 Dr. W.J.K. Harkness, Director of the Ontario Fisheries Research laboratory, established a field station in Algonquin Park. Among the research, perhaps the most important of all, was the discovery that Lake Trout were reaching legal catch size before their spawning size. In short, it would be possible to fish a lake out legally. The Department of Lands & Forests then altered the fishing regulations. Among these changes smaller lakes like Happy Isle and Merchant were closed every second year in order to give the trout a chance to spawn. The success of such a program was dependent upon one’s viewpoint. Park regulations no longer follow such a policy. For the art enthusiast, Robert Bateman was inspired in his painting while working at the research lab.

In 1942 Professor J.R. Dymond, a biologist/naturalist, was asked to take some scouts on a hike. Some of the local cottagers on Smoke Lake got wind of the hike and asked if they might tag along. This proved so successful in generating interest that F.A. MacDougall, in 1944, now Deputy Minister of Lands & Forests, asked Professor Dymond to plan a nature program for park visitors emphasizing Algonquin as a sanctuary. Dymond set up a temporary nature centre at Canisbay Trail and nature hikes were conducted at the Cache Lake recreation centre. Evening programs, including slide and movie presentations soon became an integral part of the park’s educational package.

And so began the guided walking tours for which Algonquin has become famous. An extension of these tours now includes many trails of varying lengths, each emphasizing a different natural theme. For example, the Beaver Pond Trail, 2 km in length, demonstrates how the beaver affects the environment. The Spruce Bog Boardwalk is a 1.5 km loop that provides a close look at the flora and fauna of a typical northern spruce bog. The Friends of Algonquin publish self-guided tour booklets and make them available at the beginning of each trail for a nominal fee. They not only provide invaluable reference material clearly describing the features being highlighted, they also make for an informative and interesting read. At least one bicycle path should be ready for this centennial celebration with another planned for the near future.

In 1953 a Visitor’s Centre was opened at Found Lake. The centre, also called the museum, housed a slide show theatre, a book store, aquaria featuring the fish of Algonquin, snakes and a walk through exhibit of park birds and animals. Outside ponds housed turtles native to the Park area. Technologically innovative for its time, by pushing a button one could hear the white throated sparrow, a warbler, a wolf, a “chica-dee-dee-dee” … among many other natural recordings of park inhabitants. In 1944, urged on by the Federation of Ontario Naturalists, the Department of Lands & Forests set aside 31.5 square miles of the Park as a Nature Reserve where no interference would be tolerated with the natural conditions for the further study of Park flora and fauna. Such a study could provide us with invaluable information. Therein lays a mystery. Whatever became of those studies?

In keeping with the original aims of the Algonquin Royal Commission Algonkin National Park (now Algonquin Provincial Park) remains a tonic to the health of her visitors as they escape the stresses of daily life remaining a place of rest and relaxation. Algonquin’s close proximity to large populated areas has been a factor attracting more visitors in this recessionary era. As for attracting foreign tourism this centennial year promises to exceed any expectation that the original commissioners may have dreamed. As a matter of fact the European influx began in ’92. Scuttlebutt has it that someone goofed concerning the centennial date and told a few travel agencies that the centennial year was in 1992.

Note: This article was first published during the summer of 1993. During the mid-‘80s Ontario entered an agreement with Michigan State to send some Algonquin moose to the Upper Peninsula for a re-introduction program At the time Algonquin moose numbered some 4000 animals; the highest population estimate ever. The museum at Found Lake was used in part as a command station where the Ministry of Natural Resources kept the media up to date.

During the Covid-19 pandemic when people were to keep their distance from each other the Park experienced a boom in visitor numbers seeking fresh air and an outdoor experience while maintaining that distance.