A Year of Celebration 1893 – 1993

On August 15, 1992 Algonquin Park officially presented the new Logging Museum to an adoring public. “The opening of the new Logging Museum, one of the two unique attractions being constructed to help celebrate the 100th anniversary of Algonquin Park in 1993, could not have come at a more appropriate time,” said Ernie Martelle, Park Superintendent and District Manager.

The other “unique attraction” presumably will be the $9.8 million Visitor Centre which will host the official 100th anniversary birthday party in May of 1993 and officially kick off the Centennial Celebrations.

Many special activities will take place during 1993 in celebration of Algonquin Park’s 100th birthday. Just how did this celebration come about? During the Park’s centennial year we will tour the past in an attempt to answer this question.

If Alexander Kirkwood can be credited with delivering the infant Algonquin into the 19th century then perhaps R.W. Phipps should be credited with the conception for it was he, as Chief Clerk of the newly created Bureau of Forestry (1833), who recommended in an 1884 report that “this area (today’s Algonquin Park) should be kept in forest as it is one of the chief watersheds in Ontario and is not suitable for agriculture.”

In 1885 Kirkwood proposed a National Forest and Park reservation in Nipissing District. Perhaps Phipps was a visionary for he believed that the plans were too conservative, the total area too small. History has proven Phipps correct for Algonquin Park has continued to expand since birth to its present size of 7600 sq. km. In 1961 Bruton & Clyde Townships joined the Park and in 1993, with the addition of Eyre Township (the McRae Addition) the Park continues to grow.

First to explore the Park’s present territory were the native peoples referred to by Champlain as “Algonquin savages.” Later the proposed park was to be called “Algonkin Forest and Park to perpetuate the name of the greatest Indian nation that has inhabited the North American continent.”

Following explorers such as Champlain and David Thompson came the trappers seeking their fortune in the golden pelt of the beaver so much in demand in Europe.

As man trapped out areas close to civilization with no eye to conservation he was forced to explore further afield in order to enrich his personal fortune. It was such as situation in Upper State New York that forced the Iroquois to invade the Algonquin and Huron territories ultimately decimating the Huron race and chasing the Algonquins from today’s Park area.

Following the trappers were the lumbermen. Using natural waterway highways for transport they ferried in supplies and floated out logs in their quest for fortune and wealth. The settlers soon followed and, for a brief interlude, loggers and settlers co-existed in a symbiotic relationship. The settlers provided fresh food products for the lumber camps offering some change of variety from the usual fare of “Chicago rattlesnake” (salt pork), beans, flour and blackstrap molasses. For their part the camps provided employment for the farmer, his horses and, perhaps, his son who could hire on as a cookie (the cook’s helper) in the off farming season. This pleasant relationship came to an end when the settlers began torching valuable timber in order to quickly clear the land for agriculture and settlement. Such waste alienated the lumbermen who watched part of their livelihood literally go up in smoke. In the meantime the trappers took a dim view of both loggers and settlers and moved on in search of a wilderness environment and prime fur.

In the 1880’s an ecological theme evolved emphasizing that man’s destruction of the forests not only marred nature’s beauty, it also upset the natural harmony and balance thus altering the climate. It also inflicted much damage due to soil erosion, destructive flooding, and the elimination of wildlife. The popular premise took hold that man was only a lifetime custodian of God’s world and therefore he had an obligation to leave it at least as well off as he had found it. Over the years that belief was to be subjected to considerable stress.

The Algonquin Royal Commission investigated the “fitness of certain territory between the Ottawa River and Georgian Bay for a national park” and deemed it to be ideal for many reasons. “It had never been settled. It was unsuitable for agriculture. It was largely an untouched domain of primeval forest and it was a chief watershed.” As an added bonus the government owned the entire territory. One hundred years later that very issue is under debate.

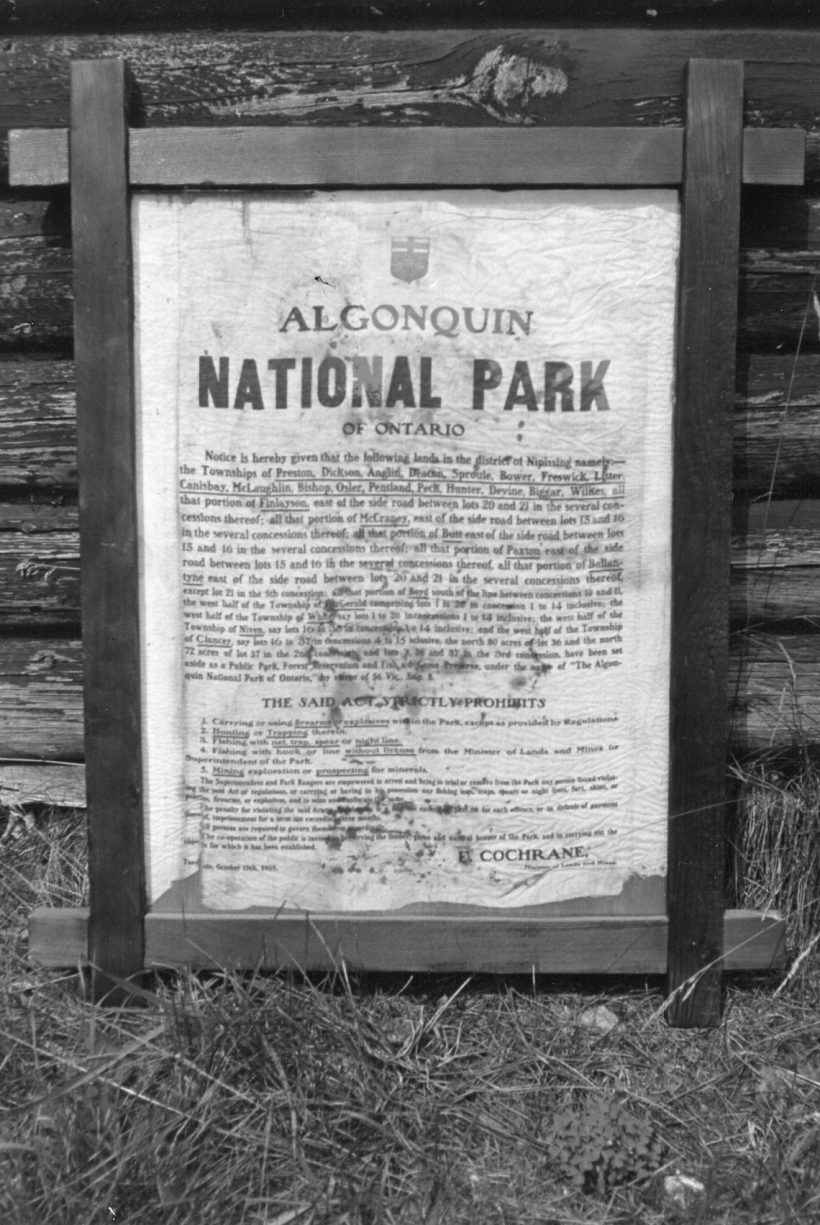

The creation in 1893 of Algonquin (sometimes spelled Algonkin) National Park focused on six major goals:

- Maintenance of water supply;

- Preservation of a primeval forest;

- Protection of birds and animals;

- A field for experiments in forestry;

- Recreation;

- The beneficial effects upon climate.

Fishing by rod and line would be permitted under licence and there would be a ten year ban on hunting. Multiple use and sustainable development, buzz words of the 1990’s, were ushered in when timber was considered to be the Park’s main source of revenue.

In 1913 a new park act changed the name of Algonquin National Park to Algonquin Provincial Park and thus brought Algonquin into the provincial fold of parks. During this time considerable improvements developed for the hard labouring lumbermen.

Camboose shanties now consisted of two rooms – one for sleeping, the other for eating. Cook stoves with water reservoirs were more efficient and required less fuel wood. Fresh meat, fruits such as raisins and prunes, cheese and jam provided improved table fare.

As early as 1896 Dr. A.S. Thompson cared for the men in Whitney lumber camps. In August 1896 Dr. Thompson visited a railroad construction camp and recounted the following:

“After supper the foreman, Jack McLeod, an experienced rock man, asked me to go with him to a rock cut 200 yards distant to have a chat while he fired two shots. As soon as he made this proposal something within me said, in tones of authority, “DON’T GO! It’s none of your business!” So I excused myself on plea of being tired. I knew something about rock drilling and the use of dynamite, but just why this warning voice came to me, I know not. There must be something in the belief of guardian angels.

We heard a shot, a deep rumbling noise indicative of large masses of rock being upheaved, and waited until dark for the second one which did not come. I was just turning in when a man rushed into the camp saying that an accident had occurred in the rock-cut. I ran along the crooked path between rocks and stumps to the cut, groping in the dark, I felt a man’s hand, struck a match, found a man lying on his back, arms extended over his head with a huge rock lying on his legs and the lower part of his body. He was quite dead. On further search we found the bodies of Jack McLeod and O’Brien, blown 30 feet out of the cut – both dead. The blast had ignited their clothes and their faces were burned…

A man living in the nearby shanty heard the noise, investigated and brought word to the camp of the accident. The man I found lying with the rock on top of him had been ordered to go home some time before the accident but he delayed too long. The accident cost the lives of three men and if I had accepted McLeod’s invitation, without doubt I would have been found. It was a sad duty to inform Mrs. McLeod, living in the camp, of the death of her good man.”

By the late 20’s many camps had proper washing facilities for the men to practice proper hygiene, a laundress and a doctor.

This article was penned in the spring of 1993.