ALGONQUIN BREAKUP

When the gentle zephyrs of a changing season first blew through the Algonquin forests their warmth issued a wake up call that signaled the coming spring. As the ice pack groaned under the vast white weight of winter the Lumbermen could hear, and feel, the impending climax to their camboose shanty sojourn. An end to their winter’s toil, working in the bush, was within their grasp. The anticipation of returning home, many to the family farm, with money in their pockets, to loved ones from whom they had been long separated, in some cases since the fall when they first left home, filled the men with excitement and added an extra measure of bounce to their steps. It was a time for the renewal of life, vigour and hope. At the same time the men felt the urgent needed to complete their pre-determined tasks of hurling the pine and skidding them to the staging areas by the lakes and rivers for once breakup began logging would be at an end.

The men of one camp had an extrasensory reason for wishing to leave. In an effort to provide variety to the usual fare of salt pork one industrious camp provided beef. The cattle had been driven to the camp where they were butchered to feed the men. Superintendent Simpson criticized the lack of cleanliness and sanitation for the offal, heads and feet of the slaughtered cattle had been left to rot. With the coming of the April thaw the men must have welcomed the thoughts of escape from such a reeky atmosphere.

For the rivermen who stayed on it was a time for adventure fraught with danger. And for many who had their baptismal bath in the hard driving icy melt waters it was the year’s inaugural wash. One driver who couldn’t recall whether he wore socks was re-acquainted with clean feet. His socks had rotted off.

Before 1893, when Algonquin officially became a park and forbade trapping those same zephyrs signaled the trapper that it was time to begin constructing his birch bark canoe and to begin pulling the traps from his line in preparation for the journey home. Henry Taylor, of Bancroft, says that he built such a canoe in four days.

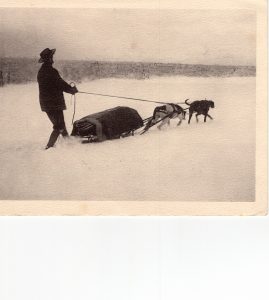

After the mid-winter fur sale the trappers headed out once more for their second season. Usually that was in January when the fur was prime. They would load their supplies on to a toboggan and snowshoe, sometimes for days, pulling their supplies behind. It was a solitary life and the anticipation of paddling his furs home must have increased the trapper’s enthusiasm for his long work days for often the trip home via canoe was much faster than the trek in to the trap line.

One of Algonquin Park’s founding objectives was to “assist the multiplication and spread of fur bearing animals”. And so trappers co-operated by live trapping animals for shipment around the world. Beaver, for example, were sent to Kentucky, Philadelphia, New York, Prince Edward Island, England, James Bay and, closer to home, Unionville, Ontario where they were released to help rebuild a depleted population. Marten were sent to Sioux Lookout. In many cases the trapper received more money for the live animals than he got for a pelt.

A favourite workhorse among the river drivers was the Pointer boat which was also known as the Drive Boat or the Bonne. It came in two basic sizes. The “baby” measured twenty-two feet and weighed in at half a ton. The much larger fifty foot model presumably saw more action on the bigger waters. Both boats were highly maneuverable and one wag quipped that the “baby” could float on a heavy dew.

John Cockburn designed and built the first pointer in the 1850’s for J.R. Booth, the lumber baron. Booth wanted a craft that could withstand extremely harsh working conditions in an environment highly charged with rushing waters and flying logs. Six to eight men served as crew on a “baby”. Their task was to sweep the shoreline for hung up logs. Pointed at both ends the pointer was made of pine planking, white cedar ribs and was steered by oars ten and a half feet long made of white spruce. The Venetian red colour was a Cockburn trademark. A pointer might last one to ten years depending on its use, or abuse. The caulked, spiked boots of the rivermen, so necessary to riding the logs, chewed up many a craft.

Henry Taylor recounts a pointer boat story involving his older brother Jim who, at the time, was foreman of a gang driving 80,000 cord of pulp logs to the E.B. Eddy company of Arnprior. The pointer cost $1.00 per foot and the cook’s pointer – complete with cook stove – measured forty feet, stem to stern, point to point. Totally loaded this pointer could carry 8500 pounds of groceries.

At each portage poles were thrust through the rings in the stove and the men carried the big, hot Findlay Range while the food kept on cooking. That range still serves up many a meal in a local hunting camp.

The men laid out logs on the portage to pull, push and roll the pointers from one side to the other. Everything else had to be carried across by hand. According to Henry, John LaValley was carrying a tub of butter on the portage when he sipped, dropping the tub, spilling its contents everywhere. LaValley quickly began gathering up the butter – dirt and all – with his bare hands, placing it back into the tub. Paddy Dillon came along and asked “What the blazes (or words to that effect) are you doing?” To which LaValley quickly quipped; “Why I’m greasing the portage, Paddy!”

Within Algonquin Park dams and chutes were constructed to overcome natural obstacles such as rapids, waterfalls – even heights of land – that hindered the movement of logs. The dam held back the rising melt waters of the spring thaw. Once there were sufficient logs the dam was opened and the logs floated down the slide, and, in some cases, up. Men were strategically placed to keep the logs from jamming up. When a log jam did occur a ‘jam cracker’ had the unenviable task of trying to loosen the key logs that were the root of the problem. This was a case in which winning might be synonymous with losing for once the ‘jam cracker’ succeeded in solving the problem he had to flee for his life. If he slipped or misjudged his escape route the free flying logs might carry him to his doom. Algonquin river shores, once the site of the spring log drives, harbour many unmarked graves of such heroic men.

The men boomed and cadged the logs in order to transport them across the lakes, first with horse power and later with the steam power of an alligator, a flat bottomed, tug-type boat. Free floating logs were corralled by logs chained together to prevent any logs from straying. Men in the towing vehicle, at first a raft with a capstan turnstile, rowed across the lake letting out line which was attached to the log boom. When they literally reached the ‘end of the rope’ a huge wooden anchor, later replaced by a metal anchor, was dropped. Then the horses would walk in circles (remember they were on the raft) and the turnstile would wind in the rope thus pulling the log boom. This procedure was repeated until the boom reached the desired destination. Eventually the alligator replaced the raft, the rowing and the horses. A rear paddle wheel drove the alligator. Heavy skids covered with steel protected the bottom while the alligator winched itself across the portages.

When several independent log drives came together, on the Ottawa River for example, a river agent or superintendent took over coordinating the drive. For ease of identification each company branded its logs. The men constructed huge rafts and pitched their tents on them. Until they reached Quebec City this would be their floating home. Sails were erected and the men manned so many 30 foot oars that the oars resembled the quills of a porcupine’s backside. The cook even had his own kitchen complete with a fire pit similar to that found in the centre of his camboose shanty.

To shoot rapids slides were built and the rafts dismantled section by section and then sent down the slide. Adding a new dimension to the culinary arts the cook often rode his kitchen section down the slide. All sections were reassembled at the base of the rapids and the drive would continue. At Quebec City the logs were loaded onto ships bound for the European market.

Eventually the railroad replaced the need for the springtime log drives. There was a time in the 1930’s when, according to Reg Blatherwick, 55 cars per day carried Booth logs out of the park. Blatherwick’s father who worked for the Grand Trunk made those daily arrangements. Logging could now be carried on throughout the year regardless of the season.

Today there remains little evidence to tell the park traveller of this bygone era. New growth forests have reclaimed their own and the rails have been lifted leaving only the rail beds for park hikers, skiers and the turtles that lay eggs there.

If you would like to learn more about this era pay a visit to the logging exhibit just inside the park’s east gate near Whitney. And, in 1993, the year when Algonquin Provincial Park will celebrate its 100th birthday, the new Museum/Visitor’s Centre and the new logging exhibit may just convince you that “You are rally there – in the past”.

This article was originally published during the spring of 1992.