Nelson A. Jeffrey died on Friday January 6, 1984 – just one week shy of his 86th birthday. For most of his life Nels, as his friends called him, lived the life of a hermit in his cabin back in the bush of Faraday Township.

Born on the family farm in 1898 Nelson grew up next to Jeffrey Lake, called Long Lake by some, off the Gaebel Road, not far from Bay Lake. Not much is recorded of Jeffrey’s childhood except to say it was interrupted by World War 1. According to Peter Freymond, Nels was a tall lad for his age and so following in the footsteps of his brother he volunteered although underage. “I guess they didn’t check his age too closely,” continued Freymond. “He was sent to France and apparently when he was marching to the front trenches he met his older brother who was being relieved. I guess it was pretty hard on his older brother who didn’t even know that Nels had enlisted and he knew what was in store for him at the front.”

As Freymond tells it Nels sent money home for his family to save for his return. However, his father used the money to purchase a team of horses to work the farm promising that they would be Nels’ upon his return.

The fears of Nels’ older brother unfortunately proved to be well founded for Nels returned from the Great War, the war to end all wars, suffering from shell shock. He was a veteran of Vimy Ridge and Paschendael. THE BANCROFT TIMES reported in 1917, “Nelson Jeffrey’s name appeared in the casualty list last week as having been gassed. He is the son of Mr. E. Jeffrey of Faraday.” And, unlike today, there was little, if any, treatment to help. To compound his situation Nels’ parents had moved away from the family farm and his brother who was running the farm refused to acknowledge that the team of horses belonged to Nels. Nels slept in the barn, perhaps to be closer to his horses. Nels was a smoker and the inevitable happened. The barn burned. Nels maintained that it was an accident. His brother thought otherwise and Nels was charged with arson. Suffering from shellshock, Nels was admitted to the Kingston asylum. However, it wasn’t long before Jeffrey escaped and returned to live the life of a recluse in the Faraday forest.

Officer Palmateer was notified from Kingston that Jeffrey had escaped and returned to North Hastings. Since Jeffrey wasn’t bothering anyone Palmateer recommended that they just keep an eye on him and leave him be.

Jeffrey built himself a cabin near Bay Lake and proceeded to live off the land. “Even his nephew didn’t have a clear idea where he lived,” recalls Peter Freymond. “Nels would make axe handles, catch trout and barter for groceries and other necessities. This helped maintain some contact with the outside world.”

Then a Game Warden ordered Jeffrey to stop fishing and Nels retreated further into himself. “He had a rough deal with too many people,” said Freymond. “He knew he could trust the animals who became his friends. At one time he regularly fed as many as 27 raccoons. Many of the groceries that we took in for Nels were to feed the raccoons. One time I brought in dog food but Nels preferred his own recipe of flour and water and the raccoons seemed to like it.”

In his cabin Nels had two stoves. “It would be freezing outside and Nels would have his door wide open,” smiles Freymond, “because he had both stoves fired up.”

“Nels had built himself a bunk bed. It was too short for him so he could never stretch out completely. He slept on the bottom bunk and a squirrel had built a big nest on the upper bunk over where Nels’ head would rest.”

It wasn’t actually until Freymond Lumber was considering the purchase of the land where Jeffrey’s cabin was located that Peter Freymond met Nelson Jeffrey circa 1959. He and George Miller were walking the land when Freymond began noticing pathways. “They’re Nels’ paths,” replied Miller who went on to explain himself.

Miller took Freymond to Jeffrey’s cabin and made the requisite introductions. At 61 and burned by a lifetime of bad inter-human relationships Jeffrey was very suspicious of strangers and Freymond was no exception. Freymond offered to help Jeffrey if help was ever needed.

One cold winter, 1959/60, Charlie Degeer and a worker were eating lunch in their logging camp when the door burst open. A starving Nels Jeffrey made a dramatic entrance asking for food. He hadn’t eaten for days; all of his food was gone.

“We had roast beef and potatoes,” said Degeer, “and we offered him what was left.” Rabbits had always been plentiful around Nelson’s cabin but when they paid him a visit there wasn’t a hare to be seen. Degeer then went to Freymond, reminded him of his promise to help, and said, “NOW’S the time!”

And so, in the winter of 1960, Peter Freymond took in the first load of supplies. Jeffrey offered to pay for the groceries with some beaver pelts. When trapping zones were started Jeffrey needed a licence to trap and sell his fur and Freymond helped him to get one.

Then Freymond and Sheldon Degeer (Charlie’s father) sought some financial aid from Faraday Township but the Reeve and his wife, who happened to be the Clerk, refused to offer assistance until Jeffrey visited the office to sign the necessary papers.

Freymond and Sheldon Degeer knew Jeffrey would never leave the security of the bush and offered to sign the papers on his behalf. The Reeve and Clerk would have none of that so Freymond, in a light bulb moment, exclaimed that he knew how he could get some financial aid. The Clerk asked “how?” and Freymond replied that he would call the three Toronto newspapers – The Star, The Telegram and The Globe & Mail. He would tell the papers that a WW1 vet in Faraday Township was starving to death. The Reeve and Clerk quickly changed their tune and agreed that the gentlemen could sign on Nels’ behalf. Thus they obtained two months cash assistance of $40. In the meantime Art Stewart obtained a Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) “burnt-out” pension which allotted $60 a month for groceries and a clothing voucher – which proved ample for both Jeffrey and his animal friends.

At a later date the Old Age Pension combined with the DVA pension provided more money than Jeffrey would ever need and so many cheques were left in the L’Amable Post Office where Jeffrey would go on foot.

The DVA sent an inspector to investigate. Art Stewart took the Inspector by Jeep to within a half mile of Nels’ place and they walked in from there. On the way they passed two potato patches that were in blossom. When the Inspector saw the cabin and nearby garden full of carrots and beans he exclaimed: “That’s fantastic. I’ve a good mind to move in with him.” The garden was fenced in to protect it from rabbits and all they could hear were the singing birds.

The Inspector encouraged Nelson to cash the cheques and to spend it but Nels stored the money in his cabin. Temptation proved too strong for some idle hands and one day a thief stole through the forest and robbed the cabin while Nelson was away. From that time Jeffrey kept a loaded shotgun by the cabin door. In fact he had to use it twice – both times to shoot a bear that tried to break in.

Old, yellowed government cheques – some as old as eight years – were honoured by both the government and the Bank of Nova Scotia.

Living off the land those many years alone in the Faraday bush was an education in itself and Peter Freymond regrets not recording the bush lore that Jeffrey passed on to him. For example, Nels had put white birch bark on his door because he knew that a porcupine wouldn’t chew it.

One year when Freymond’s aunt and uncle from Switzerland were visiting (Albert and Martha Cardineaux) he took them to meet Nels. It was after this visit that Peter’s aunt nicknamed Jeffrey the “Man of the Forest.”

Because Jeffrey’s health was failing Lou Freymond and Tim Pilgrim, both teenagers, made daily trips to check on him. They had hoped to take Nels to the Local Red Cross Hospital in Bancroft for medical care but he refused and Dr. H. Christiansen confirmed that Nelson could not be removed without his consent.

On Friday, January 6, 1984, Peter Freymond dropped in on Nelson in the morning and found him lying on the floor in failing health. That afternoon, about 3:30, Freymond again returned only this time the cabin was cold and Jeffrey was dead, once again upon the floor.

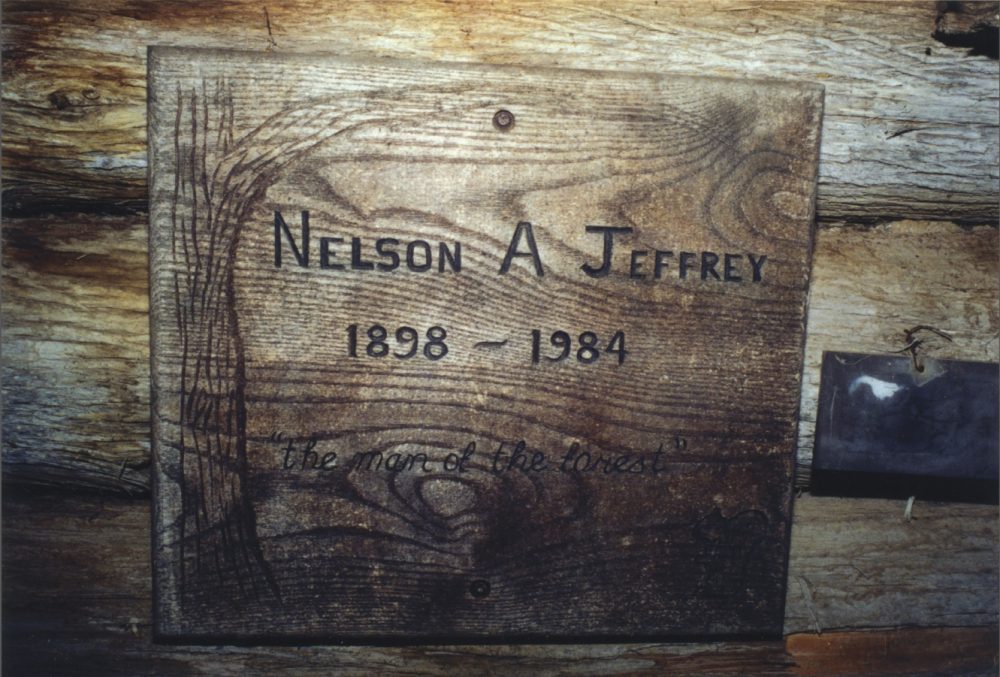

Following cremation Nelson Jeffrey’s ashes were returned for burial around the cabin. Serge Tenthorey, a family friend and wood carver, made a wooden marker showing a big tree with a squirrel. The plaque reads: Nelson A. Jeffrey, 1898-1984, “The Man of the Forest.”