EARLY LIFE IN ALGONQUIN PARK by B.M.

Trapping, hunting and fishing played an important historic role in the evolution of Algonquin Provincial Park as we know it to-day. Like a path from the past these passions have woven a common thread through the forests of time. It was the trapper who valued the raw wilderness – pristine and unchanged except in a natural way; relatively untouched by mankind. Debatably, it was common ground for the trapper and preservationist for with the arrival of the lumbermen and pioneering settlers the forests would never be the same again. To the lumbermen money grew on trees and Algonquin was prime for harvest. To the settler the trees were an impediment to settlement, to agriculture and to their livelihood although settlers did make money selling trees and supplies to the lumber camps.

Trapping, in the pre-park era and the pre-trapline era, was as well organized as a ‘dog’s breakfast’ for anyone could set a trap anywhere and they would if the price was right. Naturally this led to inevitable conflicts and eventually to the mandatory trapline.

Of course Algonquin was first known in 1893 as Algonquin National Park and although trapping was banned it didn’t deter poachers. I recall a tale in which a Park Ranger was trailing a poacher and during the night the poacher stole the Ranger’s boots, which presumeably were a good fit, and left his old worn out ones in exchange.

In an attempt to resolve the aforementioned trapping conflicts the provincial government set up zoned trap lines along the Park’s boundaries in the Huntsville and North Bay Districts. These registered traplines granted exclusive rights to the trapper who was encouraged to harvest the highest possible yield of fur while conserving enough young for the future. In this manner trappers and conservationists had much in common.

The registered traplines excluded the opportunistic quick rich players who were only interested in the money. The better the trapper maintained the trapline and protected the resource the better his, or her, financial security. Investment in the resource was investment in the trapper’s well being. And, it helped curtail poaching in the Park for the trapper was always on patrol looking for trespassers.

Eventually the use of registered traplines spread throughout the rest of Ontario. The principle of conservation in trapping, to use the resource wisely, not only encouraged the registered trapline concept to spread thoughout the remainder of the province, it became a model for North America and ultimately the globe.

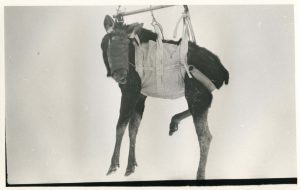

Readers are probably aware of the significance of the beaver not only to trapping but to the development of North America. Beaver were live trapped and transferred to repopulate the Mooseonee/James Bay territories where over trapping had threatened their existence. Similar ventures sent beaver throughout North America, South America, Europe and Asia in keeping with a Park objective – “The multiplication and spread of fur-bearing animals.” The fact that good money was to be gained encouraged this policy for initially Algonquin Park attempted to be self-sustaining financially and the impact on the park populations was minimal.

In 1912 the Superintendent Report stated that: “beaver were sent to Kentucky, Philadelphia, England, and P.E.I. netting the Park $5959.05.”

As an aside, in July 2001 the Outdoor Writers of Canada sent me to the Scouting Jamboree at P.E.I. I met trapper Hilton Bryanton (and also astronaut Mark Garneau now an M.P.) who had a trapping booth. Of interest, all of the materials Hilton was handing out were from Ontario. I provided Hilton with a copy of my book “the Algonquin Centennial Series” which mentioned that live beaver had been sent to P.E.I. as previously mentioned. Later that year Hilton was at a meeting with the Minister of Natural Resources for P.E.I. when the Ministry asked where the beaver on P.E.I. came from?

Well, noone at that meeting knew; until Hilton spoke up, said “I know” and then informed them.

In its own manner the beaver has involuntarily contributed to the continued existence of the wolf in Algonquin Park (A.P.) for it makes up as much as 50% of a wolf’s diet. A wolf will patiently wait hours to ambush a beaver leaving the pond in search of food and apparently the beaver has poor eyesight.

The Algonquin Royal Commission, in its opening recommendations, suggested that “Rangers should be provided with guns for self-defence and might be allowed to supplement their remuneration by killing wolves for the $10.00 a head bounty but they should not be allowed to kill or trap game or any other animal.”

That philosophy was to remain somewhat flexible through the Park’s formative years. When Superintendent Peter Thompson stated, in reference to deer protection, that the “wolf has no beast of prey to make war upon him…I hope…to get rid of these pests,” he started a vendetta that was to last well into the 20th century. On December 15, 1972 came the realization that man could not exterminate the wolf; in fact it plays an important role in wildlife management. In A.P., save the scholars who study them, the wolf is largely left alone.

Following his sudden death on September 5, 1895 at Canoe Lake H.Q. Peter Thompson was replaced by John Simpson who immediately re-introduced caribou to the Park. Due to a lack of manpower scandal broke out as Park Rangers were accused of poaching. Simpson was sacked and replaced by George Bartlett who instantly increased the number of Park Rangers from four to nine. Bartlett, an alleged favourite of lumber Baron J.R. Booth, was hired to put the park in order. Under Bartlett’s leadership the Rangers continued to trap attempting to make the Park self-sufficient but trappers complained bitterly that the Ranger’s ‘selective trapping’ was unfair and so, finally, in 1918 trapping in A.P. was banned for all. However live trapping continued with the most dramatic example taking place in the 1980s when several moose were transported to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (U.P.) and successfully re-introduced.

NEXT – Hunting in A.P.