SOME SILVER LINING by BARNEY MOORHOUSE

Master Corporal (MCpl) Chris Downey and Petty Officer 2nd Class (PO2) Douglas Craig Blake were both best buds and teammates of an explosives ordinance disposal (EOD) unit in Afghanistan. On May 3, 2010, “It was Craig’s turn to be ‘number one,’ the main guy diffusing the IED (improvised explosive device). He did an amazing job and we accomplished what we set out to do,” wrote Downey. During the 2 km return trek to their vehicles they unintentionally set off another IED. PO2 Blake died instantly. Critically wounded, Downey suffered shrapnel wounds, burns and lacerations to his thighs, upper body and face; a collapsed lung; a broken, shattered jaw and right hand; and two aneurisms. In addition, he lost part of his upper lip, all of his front teeth and his right eye. Downey could not walk, talk or see.

Air-lifted to Kandahar Air Field, doctors stabilized him before sending him to an American hospital in Germany. Downey said that only his left hand functioned. “I would make a thumbs up sign to communicate.” He had a size 8 tracheotomy – “the biggest there is” – and initially couldn’t talk. Until, one day, he discovered that by tilting his head a certain way he could.

“How in the hell?” uttered a shocked doctor when Downey first talked.

“He never shuts up,” said his mom.

“When I told my dad a joke he told the doctors that I was going to be alright.”

Downey was determined that when he returned to Ottawa he would not be carried off the plane. He would walk. And so, with gritty determination and physiotherapy, he made himself walk about the hospital building up his stamina.

“I found the hospital gift shop and bought a couple of beer steins. The medics accompanying me to Ottawa smilingly said I was their first casualty to take home a hospital souvenir.”

Two weeks later he flew to Ottawa and walked into the hospital.

“The nurse looked at me, then my medical records, then back at me and asked if I really was Master Corporal Downey?”

I first met the promoted Sgt. Chris Downey at the Roots of Hockey Classic Pond Hockey Tournament fundraising dinner on Friday, January 23, 2015. The weekend, featuring 30 teams and four natural rinks, is a four on four format competition located at the Batawa Lions’ Centre in Batawa and is organized by CFB Trenton in partnership with Scotiabank and Scotia McLeod. It is open to both military and civilian teams. Funds raised support the Trenton Memorial Hospital Foundation and Soldier On. Radio personality Paul Ferguson introduced Just for Laughs comedian Dave Hemstad who flew in from Banff, singer/songwriter Francine Leclair who performed her song “I Soldier On” (“Je Vis Sans Limites”) which was inspired by Sgt. Downey’s experience, and, of course, Sgt. Downey who flew in from Amsterdam where he had been on course.

DOWNEY SOLDIERS ON

Downey, 34, teaches explosives disposal at Canadian Forces Base Gagetown, N.B. “I have been fully re-instated to active duty with no restrictions,” he proudly told me.

Just how, you may well ask, did Chris Downey progress from being blown up by an IED to teaching?

Two words. “Soldier On.”

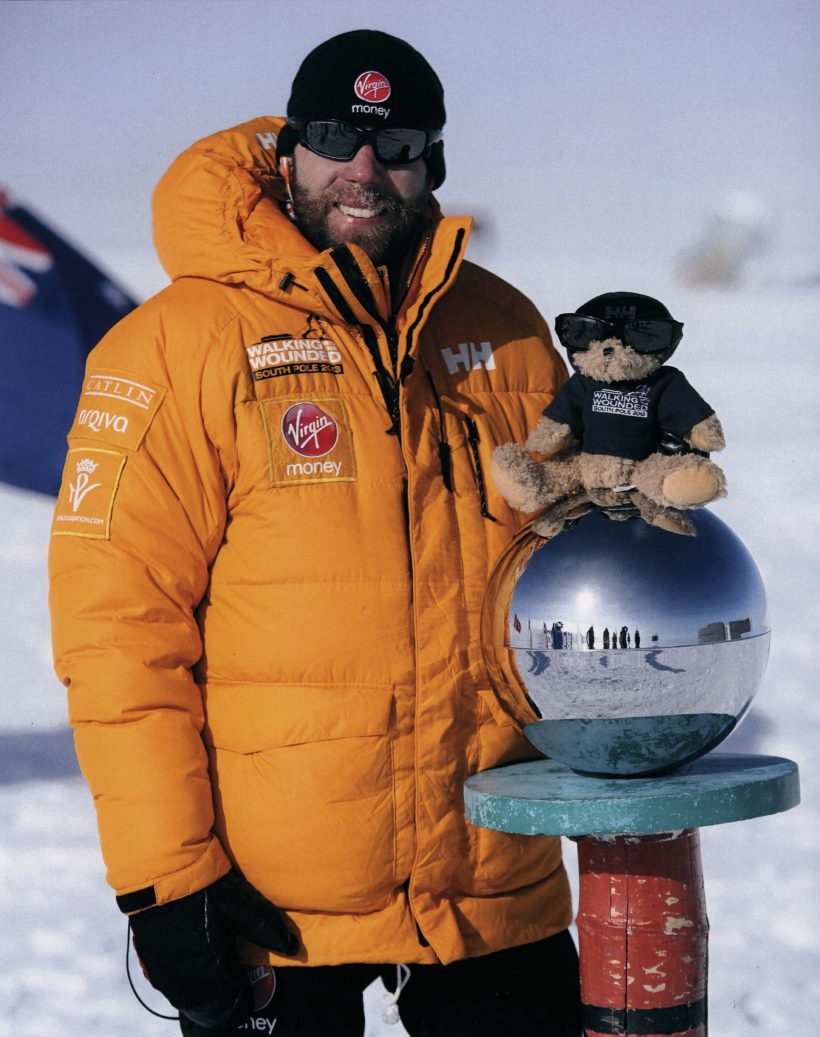

The Canadian organization, “run by wounded vets from the Major down” (Downey), has played a pivotal role in Sgt. Downey’s recovery – physically, psychologically and socially. In 2013 he was one of two Soldier On candidates invited to participate in the Walking With The Wounded (WWTW) Allied South Pole 2013 Challenge. WWTW is a U.K. organization that stages “extreme expeditions to illustrate the extraordinary determination and courage of the injured.”

Did I mention that HRH Prince Harry participated?

“He was like any other soldier,” said Downey. “He packed his own gear and acted like the rest of us.” Also participating were a few ‘celebrities.’ Such as British actor Dominic West (The Wire) who shared a tent with Downey.

“Chris is amazing,” said West. One day, he recalled, the group decided to stop short of its daily goal. Downey had already collapsed once but had insisted that they push on. West was ready for a break. “But Downey, the bastard, insisted that we carry on and collapsed again.”

During the 313 km trek to the South Pole Downey commented that “our guides said these were the worst conditions that they had ever seen.” Sgt. Downey’s self-effacing humour which permeated his presentation helped him face his challenges. “It took us 3 hours to melt the 2 litres of water that we needed each day.” They burned 8300 calories a day while consuming only 5500. Skiing and dragging their 180 pound sleds was constant. When they finally saw the buildings at the South Pole they learned they still had 22 km to go and were disheartened that they would have to camp out yet another “night” (the sun shone 24 hours) before getting there. They celebrated their arrival by “running around the world.”

Following the expedition, while in England, they were introduced to Her Majesty, the Queen. “Harry always called her Granny so when I was introduced I said “Hi Granny’ and shook her hand.” Only the “guy in charge of protocol glared at me.” It would be a master of understatement to say that Sgt. Downey was most impressed with the Queen and Prince Philip.

Since Antarctica, Downey joined the WWTW in 2014 to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro. “It rained for the first 30 hours. My stuff never did dry. But where else can you boast that you enjoyed eating popcorn at 4000m?”

Needless to say, the camaraderie that developed during the South Pole trek has created a pool of friends for life. “I still hear from them,” said Downey who reminds us that recovery is constant. “Sometimes we have a bad day.”

Part of his recovery therapy involves writing and public speaking. Encouraged to tell his story, Downey has evolved a new sense of self-confidence.

Recently, he became engaged. “Everyone wants to attend.”

Downey doesn’t regard himself as a motivational speaker. “It’s an important part of my recovery,” he said. But, if someone in the audience benefits – “then that’s a bonus.”

I had to ask. When he signed up, at 19, with the RCAF – did he anticipate being an IED operator – the “guy in a bomb suit?”

“I didn’t know the trade existed.”

A Master Corporal at Cold Lake took Downey to a demonstration. “After that first explosion, I was hooked,” adding, “My mom doesn’t get it.”

In discussing his teaching assignment at Gagetown, he said that his students can see the realism, with an emphasis on the negative, of diffusing an IED. I leave Sgt. Downey to conclude this article.

“When I woke up in the hospital in Germany, I made a promise to Craig that I wouldn’t waste a single minute of my life, I will not waste this gift. He gave his life and saved mine. We had talked about completing a physical challenge together upon our return home, so this South Pole expedition was another opportunity to honour Craig.”