A 7-point plan to save Ontario’s moose

A longtime friend used to sit on Ontario’s provincial Fish & Wildlife Board. The annual moose headache caused him to comment, tongue firmly embedded in-cheek – “just kill all of the moose and that will end this problem.” The moose issue never lets up.

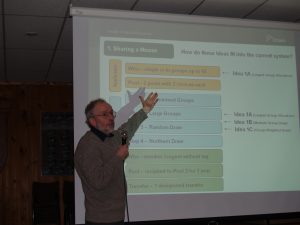

Retired moose biologist Alan Bisset has spent the past 18 months chronicling the reasons Ontario’s moose population continues to decline and he has offered the province a seven-point plan on how to fix the situation.

There is an immediate and urgent need to change the way Ontario manages the provincial moose population before the resource faces irreparable damage. On Oct. 22, 2022, Sudbury.com published an article with unequivocal evidence that, for the past 40 years, MNRF has been planning moose harvests that exceed their own guidelines and permitted harvests that exceeded those planned. Simply put they have accepted and condoned overharvest. This is the most likely reason that the moose population has been declining. It is the only thing that they can control. The evidence suggests that if the ministry continues with the current management strategy, they risk continued population decline and loss of benefits from moose for decades to come. With closed season, the inevitable result of mismanagement, the population will not increase as it did in the 1950s because there are few refugia from which moose can emigrate (even from parks, because most park populations are low through habitat loss).

KILLING SUCCESS WILL INCREASE FASTER THAN THE POPULATION CAN GROW

A seven-point plan, if implemented, should rebuild Ontario’s moose population to levels that are ecologically sustainable through real “adaptive management.” Those words are used on almost every other page of MNRF documents, but I have seen absolutely no evidence that it has been practiced. First is the use of management units east (“test”) and west (“control”) of Algonquin Park to demonstrate that controlling calf harvest is important. I absolutely agree with limited calf harvest based on the successful programs in Norway and Sweden. The evidence presented by BGMAC (the Big Game Management Advisory Committee) is faulty at best, and part of the conclusion is incorrect.

THE PLAN:

1: In the absence of sound scientific evidence, go back to proven age — sex structures in the harvest — roughly 50 per cent bulls, 15 to 20 per cent cows and 30 to 35 per cent calves. If MNRF really does use adaptive management, they should try different strategies in different Moose Management Zones. I read a recent paper that suggests a “one size fits all” strategy would be inappropriate for Ontario. The only paper I’ve seen supporting low calf harvest does not directly apply to Ontario, but it suggests that traditional rates are better to optimize the harvest yield, which seems to be Ontario’s goal.

2: Get the harvest under control. A chart shows that there is no relationship between tags and harvest. There is no control. Since the planned harvest exceeds the actual harvest in recent years, let’s assume that it is just poor planning. The first step is to reduce the planned harvest at least to the actual harvest. This means a considerable reduction in tags.

3: Return to group applications. I expect they were abandoned because of the abuse of tag transfers. OMNR, with OFAH support, screwed up the original tag transfer policy by letting anyone transfer tags before the season. I wrote the original policy, and MNRF have sort of returned to it with transfers “for reasons that could not have been predicted at the time of application”. OMNR/MNRF knew it was a mess for 35 years and did almost nothing about it. Instead of fixing the problem when it was first discovered, with a proper policy, they ignored it, then abandoned it. With group applications (and an effective tag transfer policy), there will be one application process, results probably by the end of June and all tags issued. I think many hunters already understand and want group applications. In a recent OFAH-sponsored webinar, Patrick Hubert, senior policy advisor, acknowledged there were problems with the allocation process and was looking for solutions. Some 4,500 tags (26 per cent) were not provided to hunters in 2021.

4: Eliminate three application units. With an effective allocation process, proper harvest planning and high TFRs there will be no tags after the first allocation step. Because hunters do not have to claim awarded tags, 10,122 tags (60 per cent) were left for the second allocation step in 2022. In 2021, 4,803 applicants entered the allocation process for their second choice WMU. Of these, 2,654 were awarded a tag, but only 1,573 (59.2 per cent of awarded, 9.2 per cent of total tags) were claimed. Similarly, 4,853 hunters entered the allocation for their third choice WMU. Of these, 1,635 tags were awarded, but only 515 tags (31.5 per cent of awarded, 0.03 per cent of tags) were claimed. I was unable to get comparable figures for 2022 because they weren’t known six months after the allocation process ended. That’s efficiency?

5: Encourage calf hunting by requiring “zero points” to get a calf tag. Tags would be allocated by a draw within units. Hunters would still gain a point with each application until they can get an adult tag. (Calves should provide about 50 kg (110 pounds) of “free” boneless meat.) Since non-resident hunters are not interested in calves, consult with outfitters about giving up some of their calf allocation to residents (not “trading them for adults”).

6: Replace the useless three-WMU hunter activity questions with three hunting season activity questions. With hunters spending different times and seeing different numbers of animals in archery, black powder, and rifle seasons, this would provide meaningful information to support multi-season management. In 1999, I opposed the three-unit questions because they contributed nothing meaningful to management decisions. Nobody was able to explain how it would be used. It has been in place for 23 years. I asked the director, who said, “Whether collecting information from a hunter about one WMU, or up to three WMUs if they hunted in more than one WMU, the information is used in the same way to support harvest plan development“. He could not explain how that was done. Just meaningless words. An average of only 0.25 per cent of hunters hunted annually in three WMUs over the past four years. About five per cent hunt in two units, but this can be assessed by using information from where folks apply for tags and where they state that they hunt most, using only a one-WMU question. Why even that is useful, as hunters move in both directions across units, still escapes me.

7: Work, really hard, to build credibility with hunters and others. I believe this is done with honesty and good management that people can see. It also means admitting mistakes.

Alan Bisset is a retired regional moose biologist and wildlife inventory program leader with the former Ministry of Natural Resources. He has written and published many papers on moose management, both internally and in scientific journals. Bisset lives in Strathroy, west of London, Ontario. You can find his other submissions by typing “Alan Bisset” into the search bar at Sudbury.com.