PART 3 BAILED OVER BELGIUM – Taffy’s Account

We took off about 10:00 p.m. with 22 other aircraft and joined the main bomber stream of about 150 planes and flew at 6000 feet to the English coast after which we climbed to our bombing height of 14,000 feet. The flight to the target was quiet, without incident. “The illuminating flames and the red and green target indicators went down and we made our run.” After dropping the bombs the bomb bay doors had only closed when canon fire and tracer bullets crashed through the fuselage. The rear gunner told me to dive to port. There was a huge fire aft of the engineer and the plane filled with thick smoke. “I was diving to port when a second burst hit us.” The starboard main plane was afire and the aileron control was shot away. The aircraft was “blazing furiously” and John “Taffy” Evans, the pilot, gave the order to bail. “As I was descending I saw the explosion made by the Halifax as it hit the ground.” (Evans)

Evans had no idea that he was near the ground until some tree tops “went whizzing past me.” Branches breaking sounded like pistol shots. A barking dog and men shouting inspired him to cautiously release his parachute. Digging a hole with his feet he promptly buried his Mae West and badges. Having lost one boot he cut some parachute silk for footwear and hid. After enduring a cold night in the forest Evans made his way to investigate some singing to be shocked at the sight of a squad of German soldiers, rifles on their shoulders, marching “toward me.” (“Incidentally it was very good singing.”) Later in the day he connected with the Belgium underground and his morale was bolstered when he was re-united with his bomb aimer Robbie Robertson.

Members of the Belgium White Army provided clothing, boots and a bicycle for each of them. Riding single file, keeping a discreet distance of 100 yards apart, they followed their guide to his house in the village of Zonoven where they were fed. At 10 p.m. they were taken to a hideout in the woods where they were joined by five Russian prisoners who had escaped from a German prison camp. An underground warren had been excavated into the bank of a small river.

In spite of language challenges the “Russians couldn’t do enough for us.” Apart from cooking all the food, one acted as a barber and shaved them every day; they shared their tobacco and cigarettes. “The day after we arrived Doug Lloyd (Wireless Operator), Danny Daniels (Navigator) and Les Board (Engineer) arrived.”

Always on guard, the Russians had a good sentry system. They went to bed underground at 9 p.m. and never got up before 10 a.m. They slept in 3s and if one wanted to roll over they all had to roll together. Food mainly consisted of soup, potatoes, black bread and jam. After a week they began the first stage of their journey home travelling to Hasselt, their bombing target. While riding their bikes Germans on a motorcycle passed by causing them to be nervous. The owner of the house where they stayed in Hasselt was connected with the Black Market and as a result they enjoyed good, plentiful food.

They travelled by tram, which was filled with German soldiers, to Liege where they picked up a new guide, found temporary shelter, enjoyed a good meal and had their photos taken for ID cards. At this time they were split up with Robbie leaving in the morning. Taffy and Doug went to another billet where they were housed and fed overlooking a convent converted to a German barracks. After the Germans arrested Taffy’s guide they were moved to another billet.

The “landlord” brought white flour, which was like gold as the bread she made was “very nice” unlike the black sticky stuff which began to turn their stomachs. The remainder of their diet consisted of potatoes, cauliflower, preserved beans and occasionally some black market meat – once from a dead horse. A heavy diet of strawberries and cherries towards the end of June also upset their digestive systems.

During the day they played cards, read, listened to the BBC and celebrated D Day convinced that their liberation was not far off. In fact, they had to wait another two and a half months.

When the Germans started searching Liege looking for young men avoiding forced labour, they moved to the Ardennes in the back of a closed lorry. An advance scout helped them avoid the Gestapo checks.

Staying in a fairly large house in the little village of Beffe their host would take them for midnight walks in the woods and they bathed in the river. In the morning they would peel potatoes and saw wood; in the afternoon they played Bridge. A member from North Wales couldn’t stand the routine. He left with a map, compass, a loaf of bread and some tobacco never to be seen or heard of again.

At 6 a.m. one day at the end of July the Germans raided a neighboring house where four Maquis (French Resistance Fighters) were hiding. During the gun battle one German officer was wounded, “two Maquis were promptly mown down by machine gun”, a third was shot escaping in the field behind the house and the fourth remained undiscovered, hiding in the cellar. The Germans torched the house.

Taffy and his group hid in the forest for four days, creeping back to the house at night for some food and one night they were soaked by a torrential rain storm.

Following a priest, they travelled by bicycle for an exhausting two day trip, overnighting in a shed and a barn. A second guide then took them to a rough cabin in the bush that was constructed from pine trees and a tarpaulin and was already occupied by three others. Their daily diet consisted of porridge at 9 a.m. and boiled potatoes with bread at 7 p.m. After 5 days they were on the move to a hunter’s cabin that featured windows, a fireplace and a table. “We constructed our own beds with trees, wire and ferns and lived in comparative luxury from August 4 to August 28.” A Belgian friend provided them a special bottle of wine to celebrate the liberation of Paris. Most afternoons they travelled a mile to swim in the river, sunbathed (“we became quite sunburned”), made model aeroplanes and enjoyed evening campfires.

One night they broke into a Rexist’s house (Belgian collaborator), and took anything of use such as wine, food, clothing, crockery… while their two Belgian friends trashed the place creating the impression that “they hated the collaborators more than the Germans.”

Their next, and last move, was to the village of Bohan where they numbered “25/30 evaders plus 4 or 5 Belgian helpers.” They could hear the Germans retreating on a nearby road as the Allied armies advanced. Sometimes allied fighter planes would strafe the convoys, sometimes killing horses. Later the villagers would cut meat off the horses, take it to the camp and “it was soon cooked and eaten – a very welcome addition to meager rations.”

One day an American scout car appeared and “could hardly believe their ears when our unkempt mob approached them speaking English.” Receiving “K” rations the evaders were taken to the American HQ, interrogated, and eventually driven to the American HQ in Paris where they were given G.I. uniforms and accommodation at the Hotel Meurice. After 3 or 4 days they were flown to London, interrogated at the Air Ministry and then sent home for four weeks of leave.

Evans concluded, “My most pleasant memory is of telephoning my sisters as soon as I got to London. They then passed the news to my parents. We had quite a reunion a few days later.”

FOR THE RECORD

Following a raid on Berlin during the night of December 16/17, 1943 (A.K.A. Black Thursday) officially 24 allied aircraft failed to return. Plus, due to severe weather and fog 32 aircraft crashed over England killing 127, injuring 34; the worst bad weather casualties sustained during WW2. The overall total for that one night was 294 killed with 14 prisoners of war.

For any given 100 aircrew in Bomber Command (1939-1945):

51 were killed on operations; 9 were killed in crashes in England; 3 were seriously injured; 12 became a POW; 1 evaded capture; and 24 survived unharmed. Not very good odds!

Germany had 20,625 anti aircraft guns and 6880 searchlights manned by 900,000 personnel. On average it required 3343 shells at a cost of 27,000 pounds, to shoot down one allied bomber. A Halifax bomber used one gallon of high octane fuel per mile; 2000 gallons weighed 7.5 tons. During the Battle of Britain 537 pilots were killed. A total of 545 aircrew of Bomber Command were killed on Nuremburg March 31, 1944. Almost one third of Britain’s war effort went into Bomber Command. And, because of the bad placement of escape hatches on the Lancaster the chances of survival in the Halifax were far better. Per 7 man crew, 1.3 survived in the Lancaster; 2.45 in the Halifax. FYI.

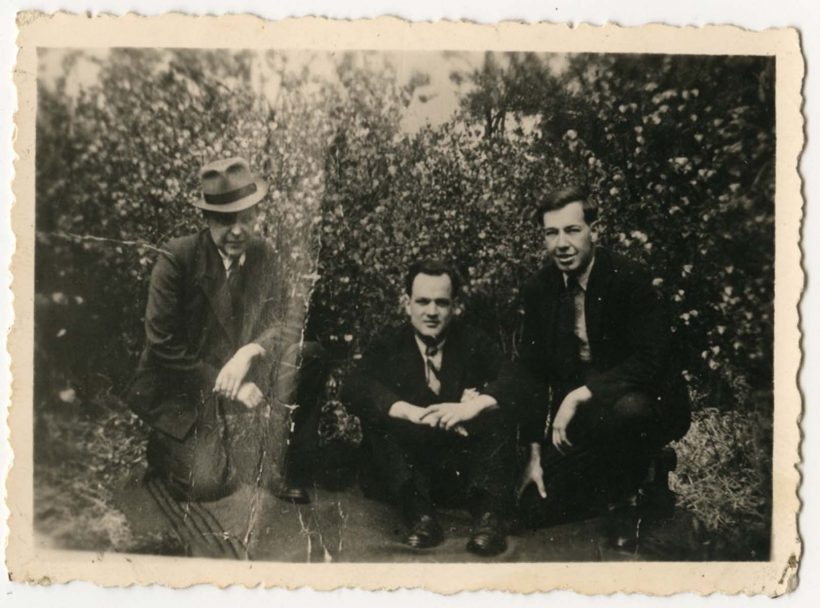

photo – left to right – Taffy, Bill, Doug.