A LIFE OF SUSTAINABILITY

“There’s a lot of talk these days, mostly from fairly high paid civil servants and politicians about sustainable development,” former editor Gary Ball wrote in the Angler & Hunter magazine in 1990. “For Ralph Bice sustainable development is a way of life.”

As best I can translate it, sustainable development really means the wise use of natural resources, use that can be perpetuated without threatening the resource being used and without damaging the environment upon which it depends.

Ball continued, “Funny thing is that most of the people who spout this trendy new term are politicians, civil servants and scientists. Politicians are a sort of necessary evil and civil servants have to get the work done. And I rather like scientists. By and large, they advance the frontiers of knowledge and stretch the boundaries of our understanding. What bothers me is that most people in these groups have never had to make a living from sustainable development. They’re all theorizing. It’s also a little odd that none are taking the time to talk to people who have lived with sustainable development for a decade or two, or even seven or eight.

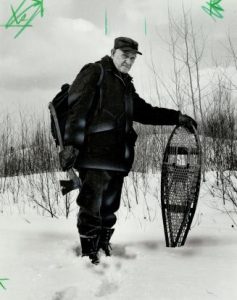

My friend Ralph Bice is one for whom sustainable development isn’t just a concept. For Ralph it’s been a way of life for at least 80 of his 90 years. He started trapping as a boy and aside from a couple of brief stints at an explosives plant during the war years he has made his living entirely from the bush. When he wasn’t trapping he was guiding anglers in Algonquin Park.

This was a man who was trapping before the Wright brothers made the first heavier than air flight. He was still trapping when men walked on the moon. Through all the years of technological explosions his trapline and guiding were his primary source of income. His fishing rod and rifle put food on the table. He has held a deer-hunting licence for 75 consecutive seasons.

Ralph changed with a changing world. In his early trapline days trappers were regarded as outlaws. They were secretive men who refused to share their secrets and techniques for fear of another trapper taking their fur.

Slowly that began to change as trappers united to gain better prices for their wild fur. From that Ralph and others became the pioneer members of the Ontario Trappers Association. They began to share their skills and techniques of fur-taking. Then they joined forces with the managers, biologists and staff members of the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. From that grew the concept of a registered trapping zone, an area where a trapper had sole rights to harvest fur, an area where a trapper could farm for fur. Ralph held one of Ontario’s second or third registered trapping zones. And he continued to trap that zone until five years ago (1985) when he turned 85. That line is trapped today by Ralph’s son-in-law and its furbearer population, bolstered by decades of careful harvesting, is as healthy as ever.

Ontario’s trappers, biologists and wildlife managers developed a furbearer management system that has been adopted in many places of the world.

It is ironic that the province, a world leader in furbearer management, bowed to pressure and banned trapping in provincial parks for reasons unrelated to sound management, biology or sustainable development.

Traplines were simply unacceptable to the anti-fur movement and to an increasingly urban population. “The government caved in.”

As a guide and trapper Ralph and thousands of others like him left the wilderness in better shape than they found it. They paved over no farmland. They left no development scars in the bush. They polluted no streams and rivers. They ringed no lakes with docks and condominiums. They built no cities, towns and high-rises in wildlife habitat. They understood too well the value of wilderness. Their lives depended upon it.

As a guide, Ralph and his colleagues sold the wilderness experience, the joy of paddling and fishing on Algonquin Park’s thousands of lakes. As trappers they sold what is perhaps the ultimate in recyclable products, fur.

A Toronto furrier described wild fur as the ultimate in recyclable garments made from surplus populations of healthy animals. “There is currently no single trapper target species in all of Canada that is endangered.”

The fur garment can be worn for 10 or 20 or 30 years or more and should fashion change can be recycled. Wild fur requires little in the way of energy to manufacture and nothing in the way of non-renewable fossil fuels to create, unlike many synthetics. And when that fur has seen its last day of use it can be simply be allowed to rot and returned to the soil.

“After listening to the furrier I got to thinking how Ralph and other trappers fit into this picture of sustainable development, of how much they could teach us about living with the planet.”

Ralph, as did other trappers, invested a great deal of time and energy taking the conservation message to classrooms. He devoted time to his work as a writer publishing four books and writing a weekly newspaper column. He has taught trapping workshops dedicated to improving trapping techniques across Canada – humane trapping methods and good fur handling.

Will society learn from these men? “Unfortunately, I think not.”

Unlike some societies we have little in the way of a tradition of learning from our elders. We tend instead to jump on any bandwagon that’s new and trendy. We will likely continue to plunder non-renewable resources, harm the environment, pave over farmland, build new highways and condominiums and ski resorts in wildlife habitat. We will likely continue to overload our lakes and waterways with nutrients and contaminants. Because men like Ralph don’t carry a string of degrees, we’ll likely ignore the things they can teach us.

If we lived in harmony with the environment as Ralph this province would be a far better place. That would be true sustainable development. We should be listening to Ralph.

AND FINALLY… From a church bulletin

Remember in prayer the many who are sick of our church and community.

Photo: by BM – Wild fur.